May the words of our mouths not be silent to truth

A Sermon by The Rev’d Dr Lynn Arnold AO

May the words of my mouth and the meditations of our hearts be worthy in your sight, O Lord, our Rock and our Redeemer. Amen.

This week, on my radio program, I have interviewed Melissa Thompson, daughter of Punch Thompson who negotiated the APY Land Rights agreement with the state government back in the early 1980s. Towards the end of the interview, which has been pre-recorded and therefore you would be able to hear it on your way home tonight if you feel so inclined, I asked Melissa about what redemption the church needs to seek for past injustices to Aboriginal people in this country. Her answer was that ‘the church was silent’ when the massacres took place.

Two weeks ago, you may recall that I preached on the occasion of the end of NAIDOC Week, a week inspired by William Cooper, a Bangerang man of the Yorta Yorta nation. In that sermon, I quoted Matt Andrews of Common Grace who wrote that:

… stories were told of landed men going on ‘blackhunts’ after church picnics of a Sunday.[1]

This was the type of ecclesial silence to which Melissa would have been alluding in her comments to me. Sadly, history confirms that there has been much truth to this accusation of silence.

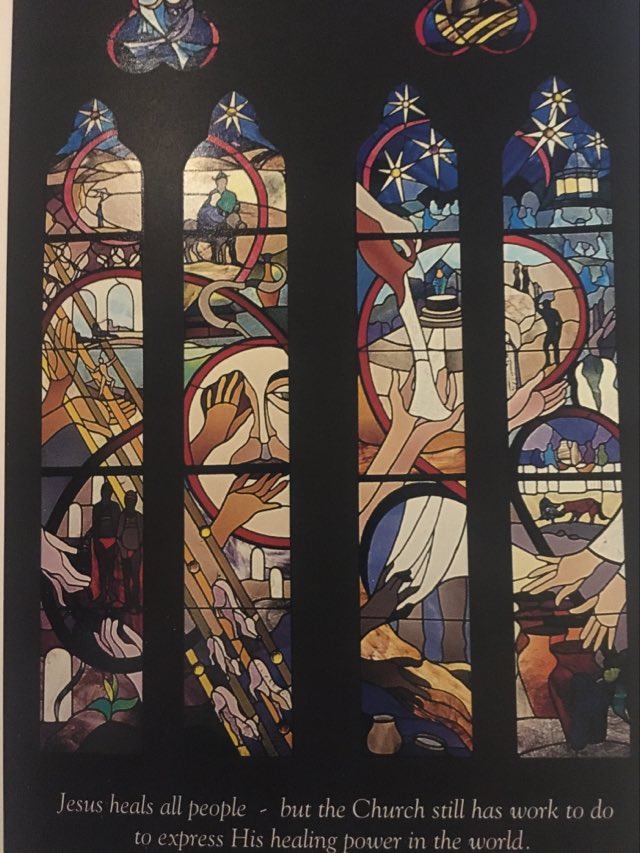

One of our clerestory windows here in the Cathedral done by Cedar Prest in the early 1990s is a silent but graphic testimony of a later problem silent for too long – black deaths in custody- the window beckons us in the church never to be silent again to such injustices.

Silence – sometimes silence is the absence of words, but sometimes it is the presence of words that drown in a dark silence of lies. Our psalm this evening speaks of this silence of lies. Listen to these words from verses 2 and 4:

They talk of vanity everyone with his neighbour: they do but flatter with their lips and dissemble with their heart. [12:2]

And,

… the tongue that speaketh proud things, which have said, with our tongue will we prevail: we are they that ought to speak, who is lord over us? [12:4]

The silence of words here is in their silence to truth. In churchly garb such silence to truth is surely condemned as being an offence against the Holy Spirit. Melissa’s call for redemption for the sin of silence to truth demands not the silence of forgetting but a silent prayerfulness seeking forgiveness and an abandoning of words that are silent to truth.

But not all was silence in the Australian church to such terrible deeds. Let me share the story of one voice that was loud with truth, a voice such as that to which the scene of injustice on our clerestory window might look for help. First let me give the context.

In June 1926, following the murder of Frederick Hay, a white pastoralist in the Kimberley region of WA, local pastoralists and police took up arms and wrought vengeance against the local Aboriginal population. The Oombulgurri, or Forrest River Massacre as it is known saw what reports at the time said were the killing of at least thirty Aboriginal people with their bodies thrown onto a bonfire and burnt. A Royal Commission in 1927 confirmed that at least eleven Aboriginal people had been murdered by the assailants; and subsequently, two policemen, James St Jack and Denis Regan, were charged with murder. However, their case never came to trial, due to the disappearance of witnesses and a reported lack of evidence; on the other hand, Lumbia, the Aboriginal man who had murdered the pastoralist in revenge for the rape of his wife, Anguloo, was convicted. At his trial he was given neither legal representation nor translation assistance; he was sentenced to death but this was commuted to life imprisonment as the court determined that Hay had provoked the attack.[2]

The Royal Commissioner, George Tuttle Wood, spoke of a ‘conspiracy of silence’ amongst the witnesses to the proceedings making his task very difficult in ascertaining the truth of what happened in those two weeks in June 1926.

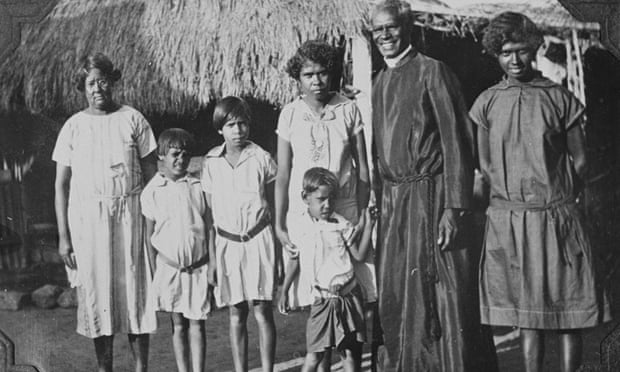

In this silent cacophony of lies and disappeared witnesses, there was one voice on behalf of the Aboriginal people of that community; a voice which directly led to the two policemen being charged. That was the voice of Rev James Noble, the first Aboriginal person ordained in the Anglican Church of Australia (in 1925). He and his wife, Angelina, had moved into the Forrest River community in 1914 as lay missionaries to develop the small mission. At the Royal Commission, Noble brought teeth and charred bones from the massacre site in support of the testimony which he gave; testimony which was based on his interactions with locals who had been present at the killings; his wife Angelina also acted as a translator for some of the Aboriginal witnesses who appeared, giving them a voice against the silence of lies.

To stand up against the silent words of lies of all who were powerful in his community must have taken great courage. But James Noble was a man of faith and he believed that the words of his mouth should be worthy in God’s sight and, just as importantly, that these words must be spoken.

Our psalm tonight speaks of the words like those James Noble used, for his words were not silent to truth but were the embodiment of truth, listen to verse 6:

The words of the Lord are pure words, even as the silver refined, which from the earth is tried, and purified seven times in the fire. [12:6]

This past Wednesday, as we do each year on November 25, we gave thanks for the life of James Noble and the fact that he wasn’t silent, letting his testimony speak in the spirit of God’s word.

The words of God – the Word of God – ‘In the beginning was the Word’ [John 1:1] – we know those opening words of John’s Gospel well; and it is at this season of Advent, starting today with the Candle of Hope, that we celebrate what came from that beginning Word:

And the Word became flesh and lived among us, and we have seen his glory, the glory as of the father’s only son, full of grace and truth. [John 1:14]

As we embark of the celebration of Advent in 2020 may our words, like those of James Noble, not be silent to Truth, may they honour that True Word who became flesh through the Nativity. May the words I used in my opening tonight, quoted from verse 14 of Psalm 19, guide us:

May the words of my mouth and the meditation of (our) heart(s) be acceptable in your sight: O Lord, my strength and my redeemer.

James Noble, his wife Angelina and their children

Partial description of this window from “Inspired Windows: St Peter’s Cathedral”, brochure available at the Cathedral shop about the Cedar Prest windows. [1994]

“The story of the Good Samaritan has its parallel in Simpson and his donkey, rescuing the wounded under enemy fire at Gallipoli, but other acts of biblical grace have less encouraging modern counterparts: Aboriginal deaths in custody, Asian refugees detained behind barbed wire in WA, and the famine victims queued up behind the contented 5,000, all make their claim upon the Christian conscience at the end of the Twentieth Century”

[1]https://www.commongrace.org.au/william_cooper#:~:text=Common%20Grace%20Hero%20William%20Cooper%20Matt%20Busby%20Andrews,then%20left%20a%20final%20challenge%20to%20Australian%20Christians

[2] https://db0nus869y26v.cloudfront.net/en/Forrest_River_massacre