Archbishop Janani Luwum (martyr)

The Very Rev’d Frank Nelson

Genesis 45: 16 – 26

Psalm 37: 23 – 35

Galatians 4: 12 – 20

Today’s first reading is a snippet coming towards the end of the long saga built around Joseph – known to many as the principal character in the hit musical by Tim Rice and Andrew Lloyd Webber, “Joseph and the Amazing Technicolour Dreamcoat”. Its catchy tunes and songs, vibrant dance scenes and hilarious and just a little raunchy portrayal of the attempted seduction of Joseph by Potiphar’s wife, tells the story found in Genesis. Joseph is the favourite son of his father Jacob, lavished with gifts, including a multi-coloured (read expensive) cloak, and something of a dreamer and fortune teller. Fed-up with his boasting his half-brothers sell him to some passing slave traders. Joseph ends up in Egypt where his fortunes eventually change; he becomes the powerful right-hand man of Pharaoh, the king of Egypt. After many years his brothers come seeking emergency drought relief from Egypt. Joseph immediately recognises them but chooses not to reveal his true identity. He plays several tricks on them, but does eventually make himself known and there is a joyful and tearful reconciliation. Tonight’s passage (Gen 45: 16 – 26) follows on as Joseph gives instructions for his elderly father to be brought to Egypt where he can live out his last days.

This reminder of the story of an estranged family and the reconciliation that followed reminded me of an incident I witnessed many years ago. The theological college I attended was in a small university town. We were encouraged to visit the various churches to see how things were done, pick up ideas and get to know the people. St Philip’s Church was in one of the worst slum areas of the city. There had been inter-gang warfare and one of the young teenage members of a gang was killed. Those responsible were arrested and sentenced to long gaol terms.

On the Sunday I was there I witnessed a sight I have not seen since. Just before the Peace, that moment in the Eucharist when, before receiving Holy Communion, we turn and greet one another as brothers and sisters in Christ, the parish priest called forward six young men. He explained to the congregation that they had been let out of prison to attend the service – their prison warder escorts were present too. The priest talked about the tragedy of a young life lost, and how not only the two rival gangs were responsible, but the whole community. These are our boys, our children, he said. They have done a terrible thing and will serve long years in prison. But today, they come to ask forgiveness of you – their mothers and fathers, uncles and aunts, brothers and sisters, neighbours, school mates and teachers. The six stood their silently, heads hanging in embarrassment and shame.

The priest opened wide his arms and spoke the liturgical greeting: “May the peace of Christ be with you all.” There was a momentary silence, and then someone began to sing. Soon the whole congregation was singing in beautiful African harmony as only the Xhosa people can do, and they surged forward to engulf those six young men in love and forgiveness. At the end of the service they were taken back to prison.

Today we live in a country and world which is much more intent on finding someone to blame, someone to pay damages, someone else to take responsibility. There’s not a great deal of the sort of forgiveness I witnessed that day.

While thinking and praying about tonight’s sermon and tonight’s readings, a news report jumped out at me because of a name mentioned last Sunday. Week by week we print those whose year’s mind occurs in the week. Mainly these are people associated with the Cathedral, a priest or bishop in the Diocese, a Cathedral benefactor, family members who have died and who we wish to be remembered. Each year, on 17 February, we have had the name Janani Luwum on the list. I am almost certain that the vast majority of people who read his name have no idea who he is – so I thought I’d tell you a little about him.

Janani Luwum was born in 1922 in Uganda, East Africa. He had no early education and looked after the family’s goats. When he did get the chance to be educated he quickly showed potential and became a teacher and then a priest. Again he showed promise and by 1969 was the bishop of the Diocese of Northern Uganda. Soon after that there was a military coup in his country and a certain Idi Amin took brutal control. Backed by the army President Amin instituted a reign of terror. Many deaths followed. Non-Ugandans, especially the Indian community who ran most of the countries shops, were expelled from the country, abandoning their shops and all their possessions. As Amin’s excesses got worse and worse, church leaders increasingly spoke out against the president.

On 16 February 1977 Janani Luwum, by now Archbishop of Uganda, called on the president to protest against the arbitrary and cruel killing of innocent people. He and his two companions were never seen alive again. It was reported they had been killed in a car accident, but in fact they had been shot on the orders of President Idi Amin. In dying doing what he believed was his Christian duty, Janani Luwum joined a long list of Ugandan martyrs going back to the 1880s when a number of Christians were killed for their faith.

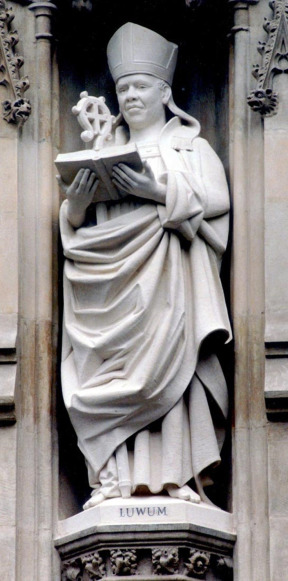

I was about to enter theological college in February 1977, and was in Lesotho with other Anglican students and our chaplain. Just before lunch one day we sat listening to the news. One of the items was a brief reference to the murder of Archbishop Janani Luwum. Philip, our chaplain, had met him the previous year and had spoken highly of him as a man deeply committed to the Gospel of Jesus Christ and to the need for reconciliation within his own country. It was a quiet and sombre meal we ate that day.Those who have been to Westminster Abbey may know that outside the main west door are ten statues – memorials to 20th century Christian martyrs. Among them is Archbishop Janani Luwum.

Four days ago the Anglican Communion News Service (https://www.anglicannews.org/news/2019/02/janani-luwums-family-and-idi-amins-kinsmen-reconcile-on-42nd-anniversary-of-martyrdom.aspx) published a report which continues the story of Janani Luwum. An Anglican priest, the Reverend Canon Stephen Gelenga, who is of the same tribe and therefore a kinsman of the former Ugandan dictator President Idi Amin, uttered an emotional apology on behalf of his family and people to the widow, family and people of Archbishop Janani Luwum. It took forty two years for that to happen – but it did, and the rejoicing is great.

Here is part of what the Reverend Gelenga said:

“As Christians from the Kakwa Community, we said we should put aside what happened in the past and let it die completely.”

He told the newspaper that Christians from Kakwa met with Archbishop Luwum’s widow at their family home in Wii Gweng where they held prayers together.

“Mama Luwum forgave us; we slept at their home, we asked for forgiveness on behalf of the people who sinned. We also want to forgive those who wronged us during the time.”

In a country and part of the world where there have been decades of conflict, some continuing to this day, that single gesture of penitence and forgiveness on the part of the families of those involved all those years ago, may serve as an example and roll model to others, including ourselves.

As we move rapidly towards Ash Wednesday and Lent, a time of soul-searching, penitence and repentance, we could do worse than reflect on words of Jesus in Matthew’s Gospel:

So when you are offering your gift at the altar, if you remember that your brother or sister has something against you, leave your gift there before the altar and go; first be reconciled to your brother or sister, and then come and offer your gift. (Matthew 5: 23 – 24)