Matthew 5:13-20

A sermon by The Rev’d Canon Jenny Wilson

In the name of God, creating, redeeming, sanctifying… Amen.

On Boxing Day last year, just hours after singing three Christmas services, our St Peter’s Cathedral Choir embarked on their tour to England, a tour that saw them singing in four cathedrals, Westminster Abbey and the Temple Church in London, finishing in New College in Oxford with Choral Evensong in the Chapel there, and a fine dinner in the New College Dining Hall. This cathedral community travelled with the choir via its generous sponsorship, its love, its prayers and its following of the story of the tour via Facebook, Christine Beal’s wonderful blog and emails. In thanks to our community, really, I want this morning to bring back the story of one of the cathedrals we visited, a cathedral that reflects in its very architecture the heart of the story of our faith, a story of death and resurrection.

One day a number of us found ourselves in a museum in Coventry. One exhibit housed quotations from a critical time in that town’s history.

“It was demoralising when you went into the town for the first time. Your town had gone, completely gone.” (Stan Smith, Coventry, 1940)

Stan Smith who spoke these words might have been an Australian who returned to his home town in recent weeks after the bushfires had raged through and destroyed his home and the homes of all his neighbours. In fact these words were spoken at another time and in another place. But the devastation was the same …Your town had gone, completely gone. The devastation was the same and the grief was the same and the wondering how to move on was, at least, a little the same.

Stan Smith lived in Coventry in England during the Second World War.

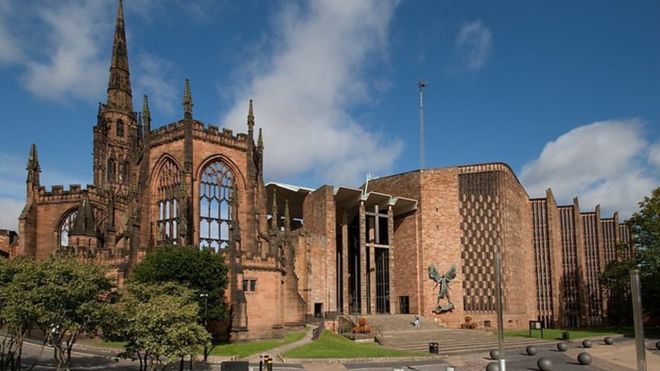

The night of the 14th of November in 1940 around Coventry was cloud free and moonlit, offering a perfect ‘Bomber’s Moon’ to over 400 aircraft targeting Coventry as an industrial centre. The operation, code-named ‘Moonlight Sonata’, marked a new form of warfare. At that time Richard Howard was Provost [of Coventry Cathedral], a post equivalent to that of Dean today. … Provost Howard was one of the four fire-fighters on the cathedral roof that night who could only watch in horror and rescue what they could of the cathedral treasures [as the bombs rained down]. … When the all-clear sounded just after 6.00am, the exhausted people of Coventry emerged to find the historic centre of the city had been obliterated. Miraculously the Gothic tower and the spire of the cathedral had survived, but all that remained of the rest of the building was the encircling outer wall.[1]

Our choir stood amongst those ruins, in the midst of that encircling outer wall, during their recent tour in England; our choristers and all who travelled with them heard the story of the old cathedral’s destruction and the new cathedral’s rising as they were led on a tour of the cathedral ruins alongside which was built the new cathedral whose foundation stone was laid by Queen Elizabeth II in 1956. Our choir then sang Choral Evensong in this cathedral for two evenings in a row. And, as they sang, a theological student who worked in the cathedral said prayers for our home and the safety of all who were caught up in the bushfires.

After the bombing, Provost Howard had immediately declared that the cathedral would rise again, as a symbol of Christ’s Crucifixion and Resurrection and of hope and forgiveness in the face of war and destruction. The cathedral’s stonemason and a member of the fire-fighting team picked up two of the great charred oak beams which had supported the roof, and bound them together in the shape of a cross. A local priest gathered three of the 15th century nails that littered the scene and made them into a cross….The cross of nails was set on an altar created from the rubble and the words “Father Forgive” were inscribed on the remaining stonework of the sanctuary. [2]

Choristers and their fellow travellers gazed at the Charred Cross and replicas of the cross of nails, from which a community of faith has grown, during their time at Coventry Cathedral. They found themselves moved deeply by such an image of cross and resurrection found in the two cathedrals, the one bombed into ruins, the other rising up at right angles at its side. Our choir gazed at the words “Father forgive,” etched in the remains of the original cathedral’s wall.

Just a few short weeks after the bombing, Provost Howard broad cast a Christmas message which included the following words: ‘What we want to tell the world is this: that with Christ born again in our hearts today, we are trying, hard as it may be, to banish all thoughts of revenge … We are going to make a kinder, simpler, a more Christ-like sort of world in the days beyond this strife.’[3]

That’s what I meant, the Apostle Paul might have said to this courageous man, this courageous community. That’s what I meant when I wrote the words we in our cathedral read this morning from his First Letter to the Corinthians:

“I decided to know nothing among you except Jesus Christ, and him crucified.” (1 Corinthians 2:2)

“Father forgive,” that Provost had written in the ruins of the cathedral, …not forgive the ones who have done this, …but forgive us all.

Yes that’s what I meant, the Apostle Paul might have said, “ … know nothing among you except Jesus Christ, and him crucified.”

You are salt, you are light, Jesus, I think, would have said to this courageous man, this courageous community.

“You are the salt of the earth; you are the light of the world.”

He says these words to us, too.

We may think that the most important words, in Jesus’ words that make up part of the Sermon on the Mount, are ‘salt’ and ‘light’ but I do not think that is so. I think the most important word is “you”.

We know all too well what Jesus goes on to say about our vocation. This is probably how we see ourselves, more often than not. As salt that has often lost its saltiness and is trampled underfoot. As light that is hidden most of the time under a bushel basket. But Jesus says to us, “you”.

God made us and has woven into us our vocation. Jesus comes to remind us of that vocation, to call into being what God made us to be. Salt of the earth, light of the world. But life can diminish us, can knock us, can raze us almost to the ground.

We have seen this in our communities as bushfires have raged through, leaving thousands of properties destroyed, hundreds of millions of animals killed, numbers of human lives lost. We have seen this as we saw people taking shelter on a beach as their nearby homes were threatened. We have seen millions of hectares of the beautiful bushland, the natural habitat of so many of our ecosystems lost.

We see this, too, when we are struck by an illness or when a loved one suddenly dies or when we find ourselves no longer able to work in a way that has given us deep meaning. Life looks like that ruined cathedral in Coventry, that burnt out town nearer to home. A town that was home, perhaps, to our family and our friends, our schools, our work, all our pastimes is gone, completely gone.

How are we to be salt and light when destruction happens? How are we to shine and give glory to God?

The Apostle Paul seems to be saying to us to know nothing but Jesus Christ and him crucified. To know that he embraced the worst of human life, a bitterly unjust trial and an awfully violent death. To know him alongside us. Whenever our lives seem to be in ruins.

Provost Howard, who surely knew awful struggle, seems to be saying that when there is much to forgive, let us try to forgive, and let us work to build a kinder, simpler, a more Christ-like sort of world in the days beyond our time of strife.

Jesus, simply says “you”. “You are the salt of the earth; you are the light of the world.” Showing his faith in us, his view of us. His understanding that we might struggle with this.

Our choir and all who travelled with them knew themselves to be deeply blessed as we stood in the ruins of a cathedral bombed all those years ago and we looked towards the cathedral built less than twenty years later through the courage and determination and faith of a community that Jesus would surely name salt and light.

He says these things to us too. You are

salt. You are light. And perhaps especially when it feels like things have been

bombed to the ground. He says these things to us. Promising his presence to

help us be so.

[1] Coventry Cathedral Guide Book p.5

[2] See Coventry Cathedral Guide Book p.5

[3] Coventry Cathedral Guide Book p.6